In its nascent stages, Islamic calligraphy emerged as a distinctive form of abstract geometric art, evolving primarily as a means to circumvent the creation of figurative representations, which Islam discourages due to concerns about idolatry or the pictorialization of religious figures. Initially, this artistic expression was not intended for the recording of facts or information. Instead, it evolved into a meditative practice for those aspiring to capture the essence of universal harmony or to manifest divine revelation. Consequently, the uniform geometric repetition of patterns in Islamic calligraphy symbolizes various aspects of the Islamic worldview and spirituality, including notions of limitlessness, discipline, and unity.

Classical Islamic calligraphy thus materialized as a form of visual art that intricately embodies the Islamic faith, significantly contributing to the broader development of Islamic civilization. The inherent anti-idolatry sentiment within Islamic art seeks to fulfill the ideal of divine transcendence, subsequently evolving into the highest aesthetic principles. This evolution led to the stylization and denaturalization of art, rendering it “non-developmental and non-figurative.” In this context, Islamic calligraphy represents a sophisticated and critically crafted artistic endeavor, reflecting the cultural and spiritual ethos of the Islamic world.

The philosophical underpinnings of classical Islamic calligraphy are deeply rooted in the interplay of dots and lines, meticulously arranged into various forms and rhythmic patterns. These elements perpetually serve to stimulate memory, referred to in Arabic as tidhkār or dhikr, through the metaphorical use of the divine pen. The Qalam (pen) in Islamic thought is considered an active agent of divine creation, facilitating the realization of the divine archetype inscribed within the Preserved Tablet (Lawh Mahfuz). This archetype encompasses letters and words that serve as paradigms, shaping the form of the world.

The act of writing with the pen in Islamic calligraphy directly symbolizes the divine act of creation. The Qalam is viewed as the instrument through which God inscribes the realities of the universe. In this sense, calligraphy is perceived as a shadow or reflection of God’s writing, an artistic embodiment of the divine script that constitutes the fabric of existence. This philosophical framework elevates calligraphy beyond mere artistic expression, positioning it as a sacred practice that connects the material world with the divine, reflecting the spiritual and metaphysical dimensions of Islamic art.

By surrendering to God’s will, the calligraphic artist perceives himself as a pen in the hands of the Divine. This perspective imbues every work and piece of writing with a sense of divinity, both in form and content. The essence of the entire Qur’an is believed to be encapsulated within Surah al-Fatiḥah, which is further condensed into the Basmalah. The Basmalah emanates from the letter ba’, and the ba’ is contained within a dot. This philosophical reduction reaches its pinnacle in the belief that Allah is symbolized by a dot. This notion is reinforced by the saying of ‘Ali Ibn Abi Talib, a companion of the Prophet Muhammad: “Knowledge is but a dot. It is the ignorant who increased it.”

An individual who establishes a deep connection with the source of this dot can become a pen in God’s hands, serving as a medium for creating Islamic calligraphy, which then transcends individual creativity to become a supra-individual art form. Within this framework, both the context of the script and the method of writing are crucial in conveying God’s words. The external characteristics of the written words, such as their placement and execution, hold significant importance. Any error in placing a dot or forming a letter could potentially alter the meaning, thereby diminishing the intended divine message.

In Islamic calligraphy, the meticulous attention to detail and the disciplined approach to writing reflect the spiritual devotion and the pursuit of divine harmony. This artistic practice not only honors the sacred text but also symbolizes the artist’s submission to the divine will, transforming the act of writing into a nuanced spiritual exercise. The resulting calligraphy is a manifestation of divine beauty and order, embodying the intricate relationship between the material and the spiritual in Islamic art.

Despite the shared reverence for the traditional objectives and significance of Islamic calligraphy, this art form does not manifest in a singular, uniform style. Islamic calligraphy encompasses a broad array of styles, including Kufic, Muhaqqaq, Naskh, Tawqi, Riqa, Shikasta, Thulth, and many others.

Among these, Kufic and Naskh are two major scripts that were developed in the early days of Islam, around the seventh century. The earliest stone-inscribed Kufic scripts were discovered in Egypt, marking the historical inception of this style. Ibn Muqla is widely recognized as the pioneer of the cursive Naskh script. His exceptional skill was lauded by Abu Hayyan at-Tauhidi, who famously remarked, “Ibn Muqla is a prophet in the field of handwriting; it was poured upon his hand, even as it was revealed to the bees to make their honey cells hexagonal.”

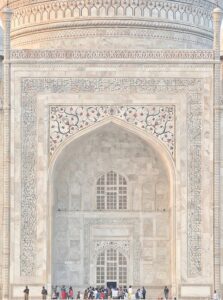

Thulth, another prominent calligraphic style, has persisted into contemporary times, commonly used in decorative and publication contexts. This style is characterized by the principle that one-third of each letter has a slope, a feature from which its name, Thulth (meaning “one-third” in Arabic), is derived. Thulth is particularly notable for its use in the intricate inlaying of jasper into the white marble panels of the architectural masterpiece, the Taj Mahal in India.

Islamic calligraphy’s diversity in style reflects the rich cultural and historical tapestry of the Islamic world. Each script not only serves an aesthetic purpose but also carries deep symbolic and spiritual significance. The varied styles have allowed for the expression of divine revelation and the preservation of religious texts across different regions and eras, contributing to the enduring legacy and evolution of Islamic art. The meticulous craftsmanship and critically carved symbolism embedded in these scripts continue to inspire admiration and reverence, underscoring the timeless beauty and spiritual depth of Islamic calligraphy.

Despite its adherence to traditional rules and rigid structures, Islamic calligraphy has never been immune to contemporary artistic influences. Far from being merely a traditional art form, Islamic calligraphy has influenced and been influenced by experimental modernism, showcasing its generative potential. This potential and its enduring popularity in the contemporary world are rooted in the intrinsic balance of Arabic lettering and script. The harmonious interplay of dots, points, edges, and curves creates a visual equilibrium that allows Arabic calligraphy to adapt seamlessly to a wide array of shapes, designs, and forms without appearing out of place or improper. This inherent versatility provides a fertile ground for creative expression.

Gertrude Stein, the renowned modernist American novelist, poet, playwright, and art collector, recognized the potential of Islamic calligraphy as a model for her own modernist experimentalism. Through her close relationship with Pablo Picasso, Stein was able to explore the intersection of calligraphy and modern art. She observed that Picasso’s identity as a Spaniard allowed him to integrate elements of Islamic calligraphy into his art without compromising his unique artistic identity. Stein argued that “Picasso’s identity as a Spaniard allowed him to apply Islamic calligraphy into his art without becoming a part of it or losing any part of himself.”

This observation underscores the adaptability and influence of Islamic calligraphy in modern art. The ability of Arabic calligraphy to maintain its distinct aesthetic while being incorporated into diverse artistic contexts highlights its felt impact on contemporary art. The intricate balance and fluidity of Islamic calligraphy continue to inspire artists across various genres, demonstrating its timeless relevance and creative potential. As such, Islamic calligraphy not only preserves its historical and cultural significance but also actively contributes to the evolution of modern artistic practices.

Contemporary avant-garde Islamic calligraphers, who draw on Islamic traditions, diverge from traditional practitioners most noticeably in their progressive approach to form and style. While some contemporary calligraphers maintain the traditional forms of Islamic calligraphy with subtle stylistic modifications, others infuse their work with personal innovations in style, form, and occasionally, content.

One notable example is Nihad Dukhan, a contemporary American-Arab artist who has developed his unique calligraphic style while preserving the movement and essence of Arabic letters. Dukhan’s approach involves simplifying the letters while adding a more stylized aesthetic, aiming to achieve a new, pure, organic form. His work epitomizes a harmonious blend of modern and traditional Arabic calligraphy, reflecting both innovation and respect for the classical roots.

Dukhan’s style represents a perfect synthesis of modernist and traditional elements, showcasing the evolving nature of Islamic calligraphy. By maintaining the fluidity and grace of traditional Arabic script while incorporating modern stylistic elements, Dukhan and other contemporary calligraphers demonstrate the adaptability and enduring relevance of this ancient art form. Their work not only preserves the historical and cultural significance of Islamic calligraphy but also pushes its boundaries, ensuring its continuous evolution and resonance in the contemporary art world.

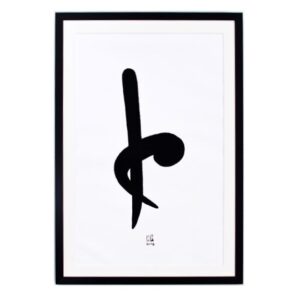

(In the given two examples, we have Nihad Dukhan’s modern work. The first piece is the Arabic word ‘Umm’ for ‘Mother,’ while the second is the Arabic word ‘Hurriyah’ for ‘freedom.)In contemporary Arabic calligraphy design, artists skillfully blend traditional forms with modern aesthetics, creating pieces that are both innovative and deeply rooted in cultural heritage. For instance, in the first given modern Arabic calligraphy design, a slightly bending vertical stroke, representing a stylized letter “A” in Arabic, symbolizes a standing mother. The rest of the design, forming the letter “M” in Arabic, depicts a child clinging to her knees. This concept is so efficiently conveyed that it is easily understood and appreciated by viewers, even those unfamiliar with Arabic script.

In another example, the word “Freedom” is depicted using modern Arabic calligraphy. The Arabic letters composing the word are stylized and arranged into an organic, abstract form. The strategic placement of the two dots above and below the letters creates a sense of movement and vibration, adding a dynamic quality to the piece.

Through his contemporary Islamic calligraphy, with its personalized touch, Nihad Dukhan seeks not only to have his voice heard but also to convey impactful divine and emotional messages. He explains, “The outward appearance of this art form represents an inward significance of spiritual purpose, incessantly making a page of Arabic script the magic mirror that arrests the desert voice.” Dukhan’s work epitomizes the fusion of tradition and modernity, demonstrating how contemporary calligraphers can preserve the essence of classical Arabic script while imbuing it with new meanings and forms.

These modern interpretations of Islamic calligraphy highlight its generative potential and enduring relevance. By incorporating contemporary elements, artists like Dukhan ensure that this ancient art form continues to evolve, resonate, and inspire in the contemporary world. Their work not only honors the historical and cultural significance of Islamic calligraphy but also pushes its boundaries, contributing to its dynamic and ongoing development.

The styles and voices of calligraphers like Nihad Dukhan and Haji Noor Din strive to balance traditional and modern frames of art. They respect the classical forms while integrating contemporary elements. In contrast, some extreme contemporary Islamic calligraphers, such as Yazan al Halwani, have ventured far beyond the traditional rules. Halwani, for instance, steps beyond merely expressing religious and spiritual messages through his art. Instead, he uses his work to convey personal voices and identities, reflecting political and social issues that were previously confined to the realm of spirituality.

Halwani is a prominent figure in the “calligraffiti” movement, which originated in Lebanon. This new art form merges traditional Islamic calligraphy with Western graffiti, attempting to achieve more than either can do alone. By blending these distinct artistic traditions, calligraffiti artists create works that resonate with contemporary audiences while preserving the aesthetic and cultural richness of classical calligraphy.

Through this innovative approach, artists like Halwani are not just preserving the heritage of Islamic calligraphy but also transforming it into a dynamic medium for modern expression. Their work addresses contemporary themes and issues, using calligraphy as a tool for political and social commentary. This evolution reflects a broader trend in the art world, where traditional forms are reinterpreted to remain relevant and powerful in addressing current realities.

The calligraffiti movement exemplifies how Islamic calligraphy can adapt and thrive in the modern world, maintaining its spiritual roots while expanding its expressive potential. By fusing the old with the new, artists like Halwani and those in the calligraffiti movement are ensuring that this ancient art form continues to evolve, resonate, and inspire across different cultures and generations.

In his “calligraffiti” art, Yazan al Halwani avoids writing complete phrases, instead using isolated letters, layering, and overlapping them to enhance the accessibility of his work. This approach marks a significant divergence from traditional Islamic calligraphy, which often focuses on the divine and sacred texts. Halwani’s art shifts the focus from these divine words to politically and socially driven fragmented letters and characters.

The navel aesthetics of “calligraffiti” introduce a novel perspective where contemporary Islamic calligraphy loses the conventional function of the word. Unlike traditional Islamic calligraphy, which adheres strictly to specific methods and content, calligraffiti embraces a more flexible and experimental approach. This flexibility allows for a broader range of expression, reflecting the artist’s personal, political, and social concerns.

By prioritizing individual letters and their visual impact, Halwani’s work disrupts the conventional expectations of Islamic calligraphy. It transforms the script into a medium for contemporary expression, blending cultural heritage with modern artistic sensibilities. This transformation challenges traditional notions of calligraphy, expanding its role from a purely spiritual practice to a platform for social and political commentary.

While traditional Islamic calligraphy is revered for its disciplined method and sacred content, calligraffiti reinterprets these elements to engage with contemporary issues and audiences. Halwani’s work, and that of other calligraffiti artists, exemplifies how the art form can evolve to remain relevant in a rapidly changing world. By doing so, they ensure that Islamic calligraphy continues to be a living, dynamic art form, capable of addressing and reflecting the complexities of modern life.

The evolution of Islamic calligraphy from traditional forms to contemporary expressions such as “calligraffiti” demonstrates the art form’s dynamic adaptability. While classical calligraphers like Nihad Dukhan and Haji Noor Din blend traditional and modern elements, artists like Yazan al Halwani push boundaries by infusing political and social themes. Halwani’s innovative use of isolated letters and abstract forms shifts the focus from divine texts to contemporary issues, showcasing calligraphy as a powerful medium for modern expression. This transition challenges the conventional functions of Islamic calligraphy, expanding its role beyond spiritual communication to a platform for social commentary. The “calligraffiti” movement, by merging classical aesthetics with modern sensibilities, ensures that Islamic calligraphy remains relevant and vibrant, continuing to inspire and resonate across cultures and generations.

References:

- Stein, G. (1939). Picasso. London and Beccles: Charles Scribner’s Sons, LTD.

- Blair, S., & Bloom, J. (2017). By the Pen and What They Write: Writing in Islamic Art and Culture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Dukhan, N. (n.d.). Modern and Traditional Arabic Calligraphy. Retrieved February 29, 2020, from http://ndukhan.com/modern-calligraphy/

- Halwani, Y. (n.d.). Yazan’s Murals, Canvases & More. Retrieved February 29, 2020, from https://yazanhalwani.com/portfolio/

- Al Faruqi, I. R. (1982). Tawhid: Its Implication for Thought and Life (R. Astuti, Trans.). Bandung: Pustaka.

Pingback: The Rediscovery of Islamic Manuscripts in Cútar: Unearthing the Lost Heritage of Islamic Spain -

Go on my sad idea We didn t worry try through