Introduction

The discovery of three Islamic manuscripts in Cútar, Spain, in 2003 provides a significant historical insight into the intellectual and cultural persistence of Islamic Spain, even after the Reconquista. These manuscripts, including a Qur’an and two other unidentified texts, belonged to Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār, a Muslim jurist and imam who lived during the turbulent period following the fall of Granada. Hidden behind a wall for over 500 years, these texts symbolize the resilience of Islamic heritage during the systematic repression by Spanish authorities, which culminated in the forced conversions and expulsion of Muslims. This research explores the historical context of the fall of Al-Andalus, the persecution of Muslims, and the cultural resistance embodied by the preservation of Islamic manuscripts. The significance of these manuscripts lies not only in their religious and legal value but also in their role as symbols of defiance against cultural erasure. The article further delves into the life and intellectual contributions of Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār, whose writings reflect both the personal struggles of captivity and the broader resistance to the obliteration of Islamic tradition in post-Reconquista Spain.

Historical Context: Al-Andalus and the Fall of Granada

Islamic Spain, or Al-Andalus, flourished from the 8th century to the 15th century as one of the most advanced civilizations in medieval Europe, where Muslims, Christians, and Jews coexisted in relative harmony. Cities like Córdoba, Seville, and Granada became centers of knowledge, where scholars from various religious backgrounds collaborated in the fields of science, philosophy, medicine, and literature (Menocal, 2002). However, this harmony was irrevocably shattered with the fall of Granada in 1492, marking the end of Muslim sovereignty in Spain and the beginning of a series of oppressive measures against the Muslim population.

The Catholic Monarchs, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, issued the Alhambra Decree in 1492, which mandated the expulsion of Jews, followed by the Edict of Expulsion in 1502, which forced Muslims to either convert to Christianity or face expulsion (Márquez Villanueva, 1984). The process of Christianization was not just religious but also cultural, as Arabic books were burned, mosques were converted into churches, and Islamic customs were banned. This period, known as the Spanish Inquisition, subjected the remaining Muslims—who had converted to Christianity but secretly continued to practice Islam (known as Moriscos)—to intense persecution (Harvey, 1996).

The Discovery of the Manuscripts

In 2003, the quiet village of Cútar was suddenly thrust into the limelight when workers renovating a centuries-old house stumbled upon three hidden manuscripts. Encased behind a crumbling wall, these manuscripts had remained untouched for over 500 years. The discovery, while unexpected, brought to the forefront the forgotten legacy of individuals like Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār, a 16th-century Muslim jurist and imam who had sought to safeguard his faith and cultural heritage during the turbulent period following the Reconquista.

Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār, a figure of intellectual and religious standing, was one of the many Muslims who refused to abandon his Islamic identity despite the mounting pressures of forced conversion. Before fleeing his homeland, Al-Ŷayyār chose to hide a copy of the Qur’an along with two other books—believed to be legal or theological texts—within the walls of his home. These texts were not merely objects of religious devotion; they symbolized an act of defiance, a refusal to allow the Islamic intellectual tradition to be erased from the Iberian Peninsula.

Cultural Resistance and the Role of Islamic Manuscripts

The concealment of these manuscripts illustrates the profound lengths to which Muslims in Spain went to preserve their religious and cultural identity. During the aftermath of the Reconquista, Islamic manuscripts were systematically destroyed in an attempt to obliterate the traces of Muslim civilization in Spain. The famous burning of books in Granada’s public square in 1499, orchestrated by Cardinal Cisneros, epitomized this cultural purge (Gómez-Rivas, 2016). In this context, the hidden manuscripts of Cútar represent more than religious texts; they are artifacts of resistance.

Al-Ŷayyār’s decision to preserve these manuscripts for posterity reflects the broader struggles faced by Muslims during the Inquisition, many of whom sought to maintain their faith in secrecy. These clandestine efforts, known as taqiyya—the practice of concealing one’s faith under duress—were widespread among the Moriscos, who outwardly practiced Christianity while privately adhering to Islam (Kamen, 1997). The manuscripts of Cútar, therefore, serve as a testament to the resilience of Islamic culture in Spain despite efforts to extinguish it.

The Literary Legacy of Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār: A Reflection on Resistance and Captivity in Post-Reconquista Spain

The recovery of ancient manuscripts from Cútar, including the Qur’an and personal writings of Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār, offers not only a window into the intellectual and spiritual currents of Islamic Spain but also a lens into the personal trials and resistance of a prominent figure during the turbulence of the late 15th century. These manuscripts, hidden for centuries, serve as a material testament to Al-Ŷayyār’s defiance against the cultural and political oppression of the Reconquista, as well as his spiritual resilience during captivity.

The rediscovered Qur’an, with its square shape characteristic of manuscripts from the Almohad period (1121–1269), reflects the cultural and intellectual flowering of Islamic Spain during an era when artistic and literary achievements reached unprecedented heights. The Almohad dynasty, which ruled parts of North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, was renowned for its architectural and intellectual advancements, fostering a milieu of creativity that continued to influence the region for centuries (Fierro, 2005). The calligraphic beauty and craftsmanship of the Qur’an manuscript from Cútar are emblematic of this legacy, connecting the discovery to a time of flourishing Islamic culture despite the encroaching Christian Reconquista.

In addition to the Qur’an, Al-Ŷayyār’s own writings, penned during a period of great personal and collective hardship, are equally valuable. These manuscripts provide an intimate glimpse into the social and political realities of Muslim life in 15th-century Spain, chronicling not only religious devotion but also the deep-rooted cultural resilience that persisted amid the chaos of war, expulsion, and forced conversion. His personal reflections and notes, some of which were scribbled in the margins of these texts, are invaluable artifacts of Islamic thought and survival in a hostile environment.

Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār: Captivity and Intellectual Resistance

Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār’s life reflects the complex interplay between individual agency and the larger forces of history. Born in a period when the Reconquista was reaching its climax, Al-Ŷayyār’s life was defined by displacement, captivity, and resistance. His journey from the fields of Asarquía to the city of Málaga, where he sought refuge from the advancing forces of Ferdinand and Isabella, was marked by the chaos of war and the eventual fall of Islamic strongholds across southern Spain.

The year 1488 marked a turning point in Al-Ŷayyār’s life. With the capture of Málaga by the Catholic Monarchs, he, like many other Muslims, found himself at the mercy of a brutal campaign of subjugation. His imprisonment in Seville, recounted in the colophon of a copy of al-Burda by al-Būṣīrī, is particularly poignant. Written on the morning of Sunday, the 27th of Dhu al-Qa’da 893 (November 2, 1488), Al-Ŷayyār’s note records his physical captivity, but it also speaks to his spiritual resilience: “…wrote it while a captive (asīr) in the city of Ishbaliyya (sic)… in the House of the Adelantado” (Fierro, 2005, p. 216).

For Al-Ŷayyār, the act of writing became both a personal refuge and a form of intellectual resistance. His pen was his strongest weapon, preserving not only the texts that formed the bedrock of his Islamic identity but also the experiences and memories of a Muslim community under siege. The colophon serves as a personal chronicle of resistance, where Al-Ŷayyār transforms his suffering into a testament of enduring faith. By anchoring his writings within the historical framework of captivity and oppression, Al-Ŷayyār’s manuscripts emerge as symbolic artifacts of cultural preservation.

The intellectual life of Muslims in post-Reconquista Spain was marked by a tension between forced conversion and clandestine adherence to Islam. The writings of Al-Ŷayyār, particularly during his captivity, echo the larger narrative of Moriscos—Muslims who outwardly converted to Christianity but secretly practiced Islam (Harvey, 1996). Al-Ŷayyār’s manuscripts, hidden for centuries, illustrate the ways in which Muslim intellectuals sought to preserve not only religious texts but also their cultural and historical identity.

In the tradition of earlier scholars such as Ibn Hazm and Ibn Rushd, Al-Ŷayyār’s dedication to the written word exemplifies the role of Islamic scholarship as a form of resistance (Menocal, 2002). Through his commentaries, marginalia, and personal reflections, he contributed to a larger effort to protect Islamic knowledge from eradication. In the face of aggressive cultural assimilation policies imposed by the Spanish crown, figures like Al-Ŷayyār took it upon themselves to safeguard their religious heritage, often at great personal risk.

The mediation efforts that eventually secured Al-Ŷayyār’s release, orchestrated by ‘Ali al-Durdūš, the chief judge of the Bishopric of Málaga, highlight the complexities of interfaith relationships during this period. Al-Ŷayyār’s eventual return to his homeland, accompanied by his wife Umm al-Fatḥ, is a testament to the resilience of Islamic scholars who, despite the upheaval of war and exile, remained committed to their faith and intellectual legacy (Fierro, 2005).

The Shadow of Forced Conversion and Religious Intolerance

Despite the semblance of stability Al-Ŷayyār found in Cútar, the political landscape was rapidly deteriorating for Muslims in Spain. The fall of Granada in 1492, the last Muslim stronghold, marked the definitive end of Islamic rule in Spain. This period also marked the beginning of systematic efforts to eliminate Islamic practices, culminating in the “general conversion” decree of 1500, which saw thousands of Muslims forcibly converted to Christianity. Granada, a former center of Islamic civilization, became ground zero for these oppressive measures, and its Muslim population was subject to intense persecution under the Castilian crown (Harvey, 1996).

Al-Ŷayyār, a witness to these dramatic changes, was likely aware of the growing hostility toward the Arabic language and Islamic scholarship. By 1502, under the Edict of Expulsion, Muslims who refused to convert were forced to leave the kingdom, and even those who converted were scrutinized for suspected secret adherence to Islam. The prohibitions against Arabic-language books, especially those of a religious or legal nature, intensified the cultural repression of the Moriscos, the forcibly converted Muslims who lived under constant threat of Inquisition (Domínguez Ortiz & Vincent, 1997).

The Concealment of Manuscripts: An Act of Defiance

Amidst this climate of fear and repression, Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār’s decision to hide his manuscripts was a deliberate and calculated act of defiance. His awareness of the Crown’s decrees, which criminalized the possession and dissemination of Arabic texts, particularly those with religious or legal content, likely influenced his decision to conceal his writings. The manuscripts, which included a Qur’an from the Almohad period and Al-Ŷayyār’s own reflections, symbolized not only his intellectual legacy but also the preservation of Islamic knowledge that was increasingly threatened with erasure (Fierro, 2005).

According to historian M. J. Viguera, the concealment of Arabic manuscripts was a common form of resistance during this period, with nearly 200 similar caches of manuscripts discovered across the Iberian Peninsula (Viguera, 1991). These clandestine efforts ensured that key religious and legal texts survived the brutal campaign of cultural annihilation launched by the Spanish Inquisition. Al-Ŷayyār’s manuscripts, uncovered centuries later in Cútar, reflect the resilience of Andalusian Muslims who, in the face of overwhelming persecution, sought to safeguard their heritage for future generations.

The rediscovery of these texts in 2003 serves as a stark reminder of the systematic efforts to eliminate Islamic culture from Spain and the enduring spirit of those who resisted. For Al-Ŷayyār, concealing these manuscripts was not merely a pragmatic decision to protect his intellectual property but a deeply symbolic gesture—a way of ensuring that his faith and scholarship would transcend his own lifetime and continue to inspire future generations of Muslims and scholars.

The Fate of Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār: A Lost Figure in the Turmoil of History

The historical record does not provide a definitive account of Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār’s later years. After the forced conversions of 1500 and the oppressive measures that followed, it is plausible that Al-Ŷayyār, like many other Muslims, fled in search of freedom. The years between 1501 and 1520 were marked by waves of migration, as entire villages were emptied in response to the draconian policies imposed by the Crown. Whether Al-Ŷayyār escaped or fell victim to the repression remains a mystery, though his manuscripts indicate a life steeped in resistance and intellectual dedication.

The act of hiding his manuscripts suggests that Al-Ŷayyār was acutely aware of the dangers posed by the Spanish authorities, and that he likely anticipated the eventual crackdown on Arabic texts. His careful concealment of these documents, which lay undisturbed for centuries, points to his foresight and his desire to protect a cultural legacy that was under siege. Whether he lived to see the full extent of the forced conversions or escaped their reach remains speculative, but the legacy he left behind—embodied in the rediscovered manuscripts—speaks volumes about his enduring faith and resilience.

The Rediscovery of Cútar Manuscripts: A Window into the Intellectual Legacy of Islamic Spain

The discovery of the Cútar manuscripts in southern Spain has unveiled a hidden treasure trove of Islamic scholarship and jurisprudence, offering scholars a rare glimpse into the intellectual and spiritual life of medieval Andalusia. Safeguarded now within the Provincial Historical Archive of Málaga, these manuscripts hold invaluable insights into the religious, legal, and cultural currents of their time. Among the recovered documents, some stand out for their profound historical and symbolic significance, particularly those authored or preserved by the scholar Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār.

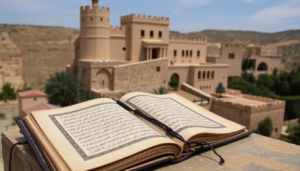

The Quran of Almohad Spain: Manuscript L14028

At the heart of the Cútar collection lies a thirteenth-century Quran, cataloged as L14028, whose square format is a hallmark of Almohad artistic and religious expression. The manuscript, with its precise calligraphy and symbolic design, serves not only as a religious text but also as a testament to the cultural sophistication of Almohad Spain. As one reads through its sacred verses, it becomes apparent that this Quran was more than a mere artifact of faith—it was an embodiment of the Islamic civilization that flourished in Spain, marked by its philosophical depth, intellectual pursuits, and artistic innovation.

The Quran itself is a reminder of how Islam permeated the lives of Andalusian Muslims, grounding their daily existence in spiritual reflection while fostering a unique blend of scholarly and artistic expression that would shape the religious and cultural landscape of Spain for centuries. The Almohads, with their emphasis on religious orthodoxy and intellectual rigor, left a lasting imprint on Islamic Spain, and this Quran offers a direct connection to that legacy.

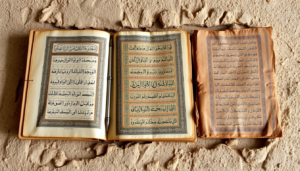

Jurisprudence and Daily Life: Manuscript L14029

Adjacent to this sacred Quran is Manuscript L14029, a compendium of Islamic legal texts that offers a more pragmatic glimpse into medieval Muslim life. The miscellany includes a wide range of subjects, from legal treatises on inheritance (farāʾiḍ) and marriage (nikāḥ) to notarial formulas and religious duties like prayer (salat). These texts reveal the intricate and highly developed system of Islamic jurisprudence that governed the lives of Andalusian Muslims, even as political and social upheavals swept through the region.

Of particular interest are the eight loose documents interspersed within this volume, each providing rich, detailed accounts of legal proceedings and everyday life in medieval Andalusia. These documents, varying in size and content, offer scholars a rare opportunity to piece together the lived experiences of the region’s inhabitants—how they navigated religious duties, legal obligations, and social customs during a period of profound change.

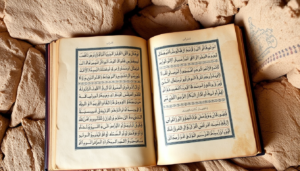

Cultural Confluence in Manuscript L14030: A Christian Substrate, Islamic Soul

Perhaps the most intriguing of the manuscripts is L14030, a text written on Christian paper with watermarks, yet entirely in Arabic. This volume exemplifies the complex cultural and intellectual exchange that characterized medieval Spain, where Islamic, Christian, and Jewish traditions often coexisted, interacted, and influenced one another. Despite its Christian substrate, the content of L14030 is unmistakably Islamic, reflecting the deep imprint of Muslim scholarship and thought on the region.

The manuscript contains a wide array of texts, including religious invocations, sermons, personal reflections, and even mystical and prophetic writings. Among these are treatises on magic and astrology, which offer a fascinating insight into the intellectual world of medieval Islamic Spain, where the lines between faith and reason, religion and science, were often fluid and intertwined. This confluence of ideas underscores the complexity of the Andalusian intellectual tradition, which embraced not only the strictures of Islamic law and theology but also the mysteries of the cosmos and the supernatural.

The Legacy of Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār: Scholar, Scribe, and Poet

Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār’s presence in these manuscripts is palpable. His contributions are especially notable in Manuscript L14030, where his role as author or scribe is explicitly mentioned in several colophons. His works reflect the multifaceted nature of his scholarship—ranging from legal and religious texts to poetic and devotional writings. Among his contributions is a stanzaic poem titled “The Necklace of the Dove” (Ṭawq al-Ḥamāma), which laments the ruin of al-Andalus, a recurring theme in the poetry of the time. Al-Ŷayyār also preserved a copy of the famous Qaṣīda al-Burda by al-Būṣīrī, one of the most revered works of Islamic devotional poetry.

Through his writings, Al-Ŷayyār captured not only the intellectual currents of his time but also the emotional and spiritual struggles of a community facing the end of Islamic rule in Spain. His lamentations on the fall of al-Andalus resonate with a deep sense of loss, reflecting the anguish of a people whose cultural and religious identity was being systematically dismantled. Yet, his poetry and prose also convey a sense of resilience and hope, a belief that the knowledge and traditions of Islamic Spain would endure, even in the face of oppression.

Preserving Knowledge Amidst Suppression: A Legacy of Defiance

The concealment of these manuscripts was, in itself, an act of defiance against the Crown’s edicts, which criminalized the possession of Arabic texts, especially those of a religious or legal nature. Al-Ŷayyār and others like him recognized the importance of preserving Islamic scholarship, even as the forces of cultural erasure threatened to destroy it. Their decision to hide these texts ensured that future generations would have access to the intellectual and spiritual legacy of Islamic Spain.

The rediscovery of the Cútar manuscripts centuries later stands as a testament to the resilience of Andalusian Muslims, who, despite the collapse of their political and social institutions, found ways to protect their cultural heritage. As historian M. J. Viguera noted, nearly 200 Arabic manuscripts have been recovered from similar hidden caches across Spain, each offering a unique glimpse into the rich intellectual and religious life of medieval Andalusia. The Cútar manuscripts, and Al-Ŷayyār’s contributions in particular, represent a significant chapter in this story of survival and resistance.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Knowledge and Resistance

The rediscovery of the Cútar manuscripts illuminates a critical chapter in the history of Islamic Spain, offering a rare glimpse into the cultural and intellectual resistance that survived in the face of overwhelming oppression. Muhammad Al-Ŷayyār’s decision to conceal these texts was not merely an act of self-preservation but a deliberate effort to safeguard Islamic heritage from annihilation. These manuscripts, hidden for centuries, underscore the resilience of Andalusian Muslims, who sought to preserve their faith and identity despite relentless persecution. Their recovery serves as a testament to the enduring power of intellectual and spiritual resistance, offering future generations a window into the rich legacy of Al-Andalus. As artifacts of defiance, they stand as symbols of the profound cultural loss that occurred and the remarkable perseverance of a civilization that refused to be forgotten.

References

- Gómez-Rivas, C. (2016). Islamic manuscripts in Al-Andalus: A window into a lost world. Cambridge University Press.

- Harvey, L. P. (1996). Muslims in Spain, 1500 to 1614. University of Chicago Press.

- Kamen, H. (1997). The Spanish Inquisition: A historical revision. Yale University Press.

- Márquez Villanueva, F. (1984). La literatura de los moriscos. Gredos.

- Menocal, M. R. (2002). The ornament of the world: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians created a culture of tolerance in medieval Spain.

- Little, Brown.Fierro, M. (2005). The Almohads: Politics, ideology, and religion. Brill.

- Harvey, L. P. (1996). Muslims in Spain, 1500 to 1614. University of Chicago Press.

- Menocal, M. R. (2002). The ornament of the world: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians created a culture of tolerance in medieval Spain. Little, Brown.

- Domínguez Ortiz, A., & Vincent, B. (1997). Historia de los moriscos: Vida y tragedia de una minoría. Alianza Editorial.

- Fierro, M. (2005). The Almohads: Politics, ideology, and religion. Brill.

- García-Arenal, M. (1997). Moriscos and the politics of prophecy in the early modern Mediterranean. Princeton University Press.

- Harvey, L. P. (1996). Muslims in Spain, 1500 to 1614. University of Chicago Press.

- Viguera, M. J. (1991). Los manuscritos árabes en España: Recuerdos de un patrimonio perdido. Revista de Cultura Árabe, 48, 47–72.

- Viguera, M. J. (1991). Los manuscritos árabes en España: Recuerdos de un patrimonio perdido.

- Domínguez Ortiz, A., & Vincent, B. (1997). Historia de los moriscos: Vida y tragedia de una minoría.

- Fierro, M. (2005). The Almohads: Politics, ideology, and religion.

- García-Arenal, M. (1997). Moriscos and the politics of prophecy in the early modern Mediterranean.